The History of Ginza Part II — Earthquake, War, and the Ashes of a District | MK Deep Dive

- M.R. Lucas

- Dec 3, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

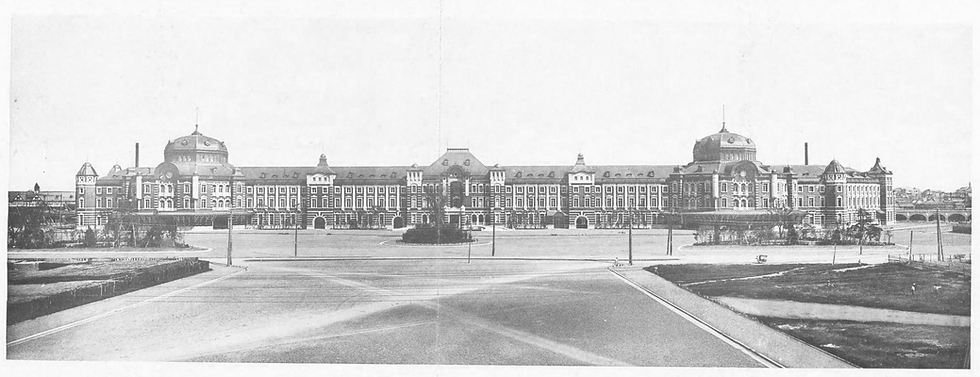

September 1, 1923. The Great Kantō Earthquake struck with devastating force, and the brick-built Ginza, once considered fireproof, collapsed into flames. Much of the district was reduced to a wasteland of rubble and ash. Yet Ginza’s merchants, who had rebuilt their world before, refused to give up. Within weeks, makeshift stalls appeared—some designed by avant-garde artists who used scavenged materials to create experimental, almost theatrical storefronts. The reconstruction became its own cultural moment.

Missed Part I? Start with:

By 1929, the district’s leading department stores — Matsuzakaya with its rooftop zoo, Matsuya with its aquarium, and Mitsukoshi with its sleek modern style — revived the area. Real estate prices surged to the highest in the country. Ginza’s nightlife boomed. About six hundred bars and cafes flickered with records, conversations, and smoky modern atmospheres. Mobo and Moga — modern boys and modern girls — strolled the streets in bold fashions that blended Tokyo and Paris, Edo and Berlin.

But the undercurrent of the era told a different story. Women’s associations marched through the streets chanting “Luxury is the enemy,” reflecting a rising nationalism that criticized Ginza’s glamour. By 1944, the streetlights had been taken down and melted down for the war effort. The streetcar rails were surrendered as scrap. Kabuki theaters closed their doors. Neon vanished. People planted vegetables in the gaps between buildings to try to survive shortages.

Then came the air raids.

On January 27, 1945, bombs hit the district. A local elementary school was hit directly. The attacks worsened on March 9–10 and again on May 25, turning Ginza into a scorched ruin. Survivors gathered in department store basements as firestorms raged overhead. Many fled Tokyo entirely, escaping to the countryside.

The war ended in August. Allied jeeps rolled down Chuo-dori. English street signs appeared. The sturdier pre-war buildings were converted into PX stores for occupation troops. Black markets spread across the ruins, selling everything from military surplus to children’s toys. Yet within months, Ginza was rebuilding. In April 1946, the district hosted its first “Ginza Reconstruction Festival,” and by the end of the year, hundreds of shops had reopened.

For a while, street stalls defined the scene — acetylene lamps hanging over makeshift counters, with bargaining sounds filling the night air. These stalls became the foundation of early postwar commerce. But by 1951, GHQ ordered their removal, citing sanitation concerns and the risk of fraud. Ginza once again prepared to reinvent itself.

In 1952, with shops returned to their original owners and the San Francisco Peace Treaty in effect, full-scale reconstruction started. Piles of air raid debris, once stacked endlessly along Showa-dori, were pushed into the old waterways and moats that had surrounded the district since Edo times. Tokyo was entering the age of the automobile. Where boats once carried goods, expressways were built.

By the 1960s, the Ministry of Construction launched a significant renovation to modernize Ginza's traffic flow. Utility lines were buried underground. Sidewalks were widened. Granite from old streetcar tracks was reused. Willow trees were removed and replaced with umbellata shrubs. New gas-style lamps were installed. The project was completed in 1968, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the Meiji era.

Then came the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the city’s economic boom. Ginza experienced rapid growth. Architectural landmarks replaced wooden postwar buildings. The Sony Building was completed in 1966, soon followed by the San-ai Building, Toshiba’s large complex, the Ginza Lion Building, and Shiseido’s modern flagship store.

Subways also expanded. By the mid-1970s, five lines intersected beneath Ginza, serving more than 150 million passengers per year. A new era had begun.

By the 1980s, Ginza was thriving once again. Corporate money flowed like champagne. Lavish parties, bold deals, and a sense of endless possibility filled the district. Banks and securities firms replaced older storefronts, transforming the daytime economy. But the bubble had its flaws: financial offices closed at 3 p.m., leaving entire blocks lifeless, and land taxes soared to punishing levels for families who had no plans to sell their heritage.

Then the bubble finally burst.

The next chapter begins with deregulation, design councils, and Ginza’s quiet reinvention in the new millennium.

→ Part III

MK TAKE

Ginza’s resilience is no accident — it follows a pattern. Through earthquakes, air raids, occupation, and rapid modernization, the district has repeatedly rebuilt itself with grit, boldness, and imagination. Part II shows Ginza at its most vulnerable but also at its most human: a neighborhood where merchants, artists, and families refused to let destruction define their future.

Let MK guide you through the echoes of Ginza’s past — its ruins, its rebirths, and the streets where resilience became a way of life.

M.R. Lucas is a writer living in Japan.

Image Credit

Wilford Peloquin, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Marie-Sophie Mejan, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Comments