The History of Ginza Part I — Silver, Fire, and the Making of Modern Tokyo | MK Deep Dive

- M.R. Lucas

- Dec 3, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

Ginza today is synonymous with elegance — an epicenter of luxury where Tokyo’s elites navigate between brightly lit storefronts and softly illuminated evenings. It resembles the city’s response to Madison Avenue or Avenue Montaigne, adapted into Japanese sophistication. But before the boutiques and mirrored glass, before the department stores and designer flags, the district was something much simpler: a reclaimed marsh that carried the scent of the sea.

The name “Ginza” dates back to the early Edo period, when Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan and established the shogunate in 1603. In the low-lying marshy area now known as Ginza 2-chome, the new government set up its official silver mint. Here, workers melted and pressed coins to stabilize the national currency for the newly unified country. Its counterpart — the Kinza, responsible for gold — was located in Nihonbashi, where the Bank of Japan would later be built.

Those who handled silver wielded privilege. The wealth generated by the mint not only enriched the state but also its officials, who became so wealthy that corruption scandals eventually led to the district’s move to Nihonbashi in 1800. Yet, the name “Ginza” persisted. Even without the mint, it had already become a symbol of commerce and wealth in the minds of Edo’s citizens.

Around the mint, specialist guilds thrived — craftsmen who mixed vermillion, families who produced scales precise enough to weigh silver and gold, merchants who minted ornamental gifts for the shogunate. Kimono sellers lined the main street. Noh actors, regarded with the same prestige as Hollywood celebrities today, kept residences nearby, adding a layer of high culture to a neighborhood already buzzing with activity. Ginza was beginning to develop its unique identity: commercial, artistic, worldly, and restless.

But as the Edo era declined, the district fell into neglect. The marshland roots reemerged in spirit, if not in fact — streets worn down, commerce fading, and the old prestige diluted.

Everything changed in 1872 when Ginza burned down.

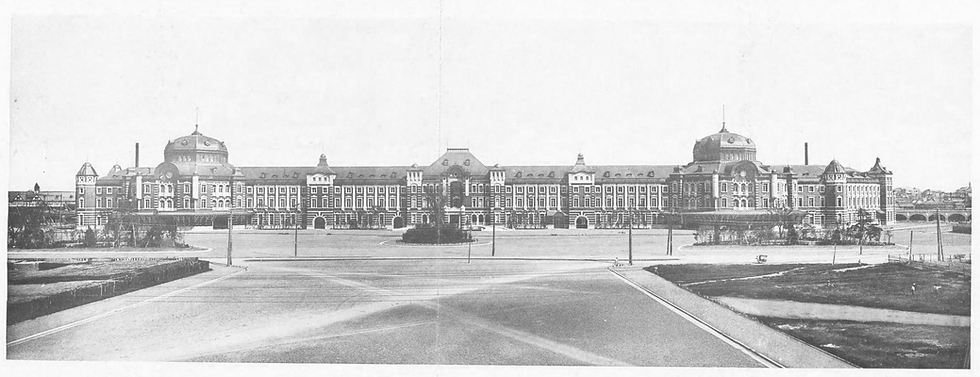

The fire that swept through the district that year destroyed nearly everything, including the remnants of its early prosperity. Yet in its destruction, the Meiji government saw an opportunity. Determined to Westernize, officials hired British architect Thomas James Waters to rebuild the area with brick. Fireproof red-brick structures replaced wooden houses. Roads were widened, gas lamps lined the sidewalks, and cherry, pine, and maple trees were planted along the orderly gridlines of the new capital. The transformation was costly — 1/27 of the government’s entire budget — but it marked the birth of modern Ginza.

It was the same year that Japan completed its first railway between Shinbashi and Yokohama. With Shinbashi adjacent to Ginza, imported goods flowed into the area. Western restaurants appeared. Watches, fabrics, furniture, and clothing dazzled curious passersby. Shopkeepers adopted glass display windows, and customers entered stores without removing their shoes — another small revolution. Ginza became the stage on which a once-isolated nation experimented with the modern world.

Publishers hurried in. Newspapers and magazines established offices among Western shops, attracted by the promise of new ideas, images, and sensations. By the late 19th century, Ginza was not only the city’s most modern district but also its most cosmopolitan.

In the early 20th century, Western-style brick buildings began to absorb Japanese life. Tatami mats spread through parlors. Cafés multiplied, driven by the novelty of Brazilian coffee. Writers, painters, and intellectuals gathered to talk, sketch, and think. Ginza became Tokyo’s own miniature Montparnasse — a neighborhood where art and literature drifted through the air like cigarette smoke.

The word Ginbura appeared around 1915, describing the act of “strolling through Ginza.” It could mean leisurely window-shopping — or, depending on tone, the swagger of young men with too much style and too little direction.

Everything appeared to be climbing. And then, once more, Ginza was set ablaze.

The next chapter begins with the Great Kantō Earthquake — and Ginza’s fight to rebuild.

→ Part II

MK Take

Ginza’s story isn’t just about luxury — it’s about reinvention. What started as a reclaimed marsh and silver mint became a testing ground for Japan’s first wave of modernity. Fire, ambition, culture, and commerce clashed here long before department stores and designer storefronts appeared. Understanding Ginza’s origins reveals something essential about Tokyo itself: the city constantly rebuilds, refines, and reimagines what it can be.

Let MK Guide you through Ginza’s layered history with comfort, clarity, and the expertise of those who know the district best.

M.R. Lucas is a writer living in Japan.

Image Credit

桜ジェリクル, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Comments