Tokyo Station: Birth of a Modern Capital — Part I | MK Deep Dive

- M.R. Lucas

- Nov 18, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

In the late 1800s, as the enthusiasm for the Meiji Restoration grew across the country, the old Edo-era infrastructure had reached its limit. Roads, canals, and post stations — once the lifelines of the Tokugawa shogunate — were starting to fade along with the memory of the samurai government that built them. Tokyo, recently transformed from Edo into the capital of a modern nation, was envisioned as the city of the future. Japan had opened its doors to the world, and the new era called for a grand gateway in return.

Railways became the vehicle for that dream. The Imperial government saw them not just as a technological upgrade but as the backbone of a unified nation. Before a central terminus could be built, however, the lines had to be connected. In 1890, the government announced its plan to merge private and state-run railways into a single national network. This ambitious effort would link Hokkaido to Kyushu and support commerce, military power, and modern life across the entire archipelago.

The transformation of Tokyo truly began in 1900 when construction of elevated tracks started threading through the growing city. Progress paused as Japan entered the Russo–Japanese War, draining manpower and resources. Yet victory in 1905 reignited national confidence. Work resumed in 1906, and by 1910, the elevated corridor was complete, paving the way for the central station the country had long envisioned.

Early design responsibilities were assigned to German engineers Hermann Rumschöttel and Franz Baltzer, whose technical groundwork laid the foundation for the developing railway network. Their plans were soon handed over to Tatsuno Kingo, a pioneering Meiji-era architect and designer of the Bank of Japan. Tatsuno kept Baltzer’s structural foundation but added his own vision: a Renaissance-inspired façade made of red brick and granite, grand octagonal domes, and a steel-framed interior that blended Western classicism with Japanese ambition.

A lively debate broke out during the construction. Should the terminus be called “Central Station,” emphasizing its role, or “Tokyo Station,” connecting it to the identity of the new imperial capital? The arguments went on until just two weeks before opening day. In the end, the city’s name prevailed.

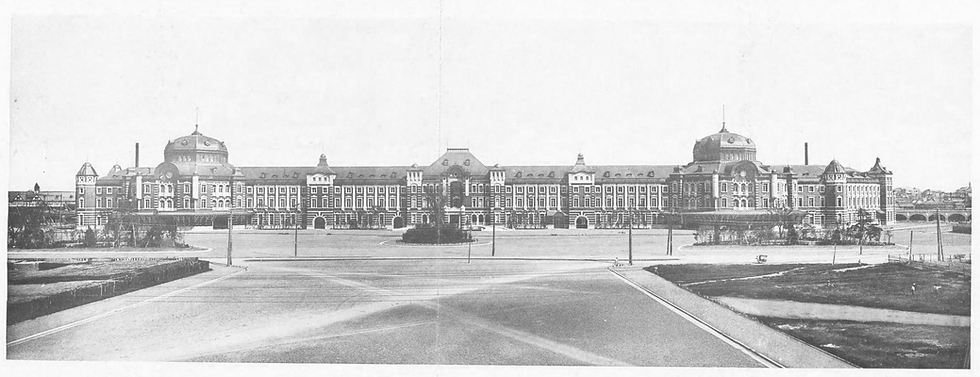

Tokyo Station opened to the public on December 20, 1914. Standing three stories high, topped with symmetrical domes, and covered in red brick and copper tiles, it reflected the architectural pride of a nation stepping onto the world stage. For dignitaries and travelers arriving from distant prefectures, the station provided a deliberate and unforgettable first impression of the capital — a rising world power asserting itself through steel, brick, and ceremony.

The opening celebration captured the spirit of the era. Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu led the event, accompanied by government officials, railway pioneers, and soldiers returning from World War I. The station represented years of ambition coming together in one structure, signaling Tokyo’s rise as a modern global city.

Just one year later, the Tokyo Station Hotel opened inside the Marunouchi building. Its 72 rooms, banquet halls, and elegant European style quickly made it a sensation. Almost always fully booked in its early years, the hotel remains one of Tokyo’s historic landmarks today — its halls restored, its atmosphere preserved.

But the optimism of the Taishō era did not erase the shadows forming beneath the surface. In November 1921, Tokyo Station became the scene of a national tragedy when Prime Minister Hara Takashi — the first commoner to lead Japan’s government — was assassinated by a 19-year-old railway switchman near what is now the Marunouchi South Gate. His death exposed the growing political extremism already infiltrating public life.

Less than ten years later, the station saw another act of violence that foreshadowed Japan’s push toward militarism. In November 1930, Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi, known for his courage and economic reforms, arrived at Tokyo Station after coming back from Okayama. As he stepped onto Platform 4, a right-wing nationalist shot him at close range. Hamaguchi survived the immediate attack but died the following year from complications related to his wound. Today, discreet plaques mark the exact spots of both attacks — easy to miss amid the busy commuters, yet haunting reminders of an era darkening by the day.

Between these two assassinations, one of Tokyo’s most devastating disasters occurred. On September 1, 1923, the Great Kantō Earthquake hit with a magnitude of 7.9. More than 110,000 people lost their lives, and over 135,000 buildings were destroyed in the quake and the fires that followed. Remarkably, Tokyo Station only suffered minor damage. Its brickwork and domes remained intact, and the building quickly became a refuge for thousands of displaced residents. At its height, nearly 8,000 people sought shelter inside, turning the proud gateway of the capital into an emergency sanctuary.

Two decades later, as World War II took over the country, Tokyo Station became an unexpected symbol of women’s labor. Under the National Mobilization Law, as men were drafted into the military, young women filled crucial roles in the rail system. More than 200 women worked at the station during the peak of the war, operating ticket gates, staffing platforms, and helping passengers. An all-girls vocational school was even established to train these workers — an institution that closed at the war’s end. Their contributions, often overlooked in history, were essential to keeping the country’s busiest rail hub running during its darkest time.

But the station could not escape the destruction of the final year of the war. On May 25, 1945, U.S. B-29s carried out one of the most devastating firebombing raids of the conflict. Tokyo Station took a direct hit. The iconic domes — symbols of imperial dignity — were wiped out. The entire third floor burned away. Flames tore through the central and southern entrances, reducing Tatsuno’s architectural masterpiece to a blackened shell.

And yet, even amid destruction, the station refused to go silent. Restoration efforts started the next morning. By May 27, trains were back in service. It was a temporary, makeshift revival to keep Tokyo moving, but it demonstrated the city’s strong will to survive.

Still, the future of Tokyo Station remained uncertain. Japan was spiritually, financially, and materially drained. The war was nearly finished. The domes were gone, the third floor erased, and the architectural symbol of modern Japan stood stripped of its former grandeur. Postwar reconstruction would create a new shape — pragmatic, subdued, and efficient. But the spirit of Tatsuno’s original masterpiece lingered beneath the surface, waiting for the day its dignity could be restored.

That restoration — faithful, ambitious, and truly monumental — was not finished until nearly a century after the station first opened.

MK Take

Tokyo Station’s history is more than just railways or architecture. It tells the story of a nation continuously reshaping itself through ambition, disaster, loss, and renewal. Its red brick walls have witnessed technological revolutions, political upheavals, natural disasters, war, and rebirth. To understand the station is to understand modern Japan — one platform, one brick, one turning point at a time.

Let MK guide you through Tokyo Station's birth as Japan's gateway to modernity, its survival through catastrophe, and its heralding of a new century.

M.R. Lucas is a writer living in Japan.

Comments